Remembering those who paved the way

As we celebrate Black History this month, we take a look back at some remarkable pioneers whose persistence, dedication, innovation and leadership have paved the way and shaped the landscape of eye and vision science.

David K. McDonogh, MD, (1821 - 1893), was a slave who, in 1838, was sent by his owner to Lafayette College in Easton, Penn., then went on to train at the College of Physicians and Surgeons (now known as Columbia University). Even though denied a diploma, McDonough was able to practice at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary and even started a practice in Manhattan’s Village neighborhood. In 2018, McDonogh was posthumously awarded a medical degree from Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons.

(Artist: Leroy Campbell; Credit: NYEE)

Charles Victor Roman, MD, (1864 - 1934), was the the son of a fugitive slave who went on to become a surgeon, professor, author, civil rights activist and historian. At age 19, while working as a public school teacher, Roman started studying medicine at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tenn. After graduatng in 1890, he opened his private practice in Clarksville, Tenn., later relocating to Dallas, Tex. In 1904, he closed his practice and went to study ophthalmology at the Royal Ophthalmic Hospital of London (U.K.) as well as otolaryngology at the Central London Nose, Throat and Ear Hospital. That same year, he returned to Meharry Medical College as a professor of ophthalmology and otolaryngology and was also installed as the fifth president of the National Medical Association. Roman later founded and became the first chairman of Meharry's Department of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology, and simultaneously served as head of the Department of Health at nearby Fisk University (now know as Tennessee State University).

(Photo credit: Public domain)

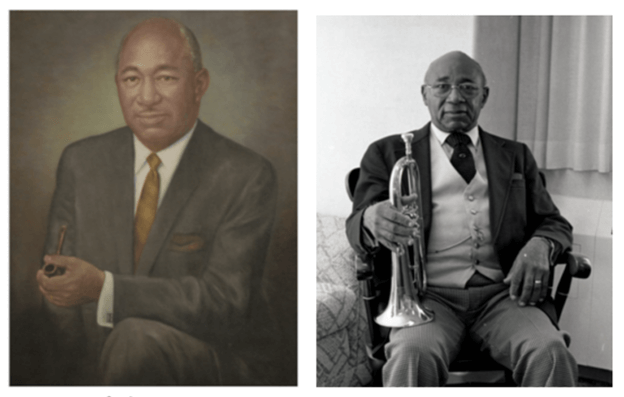

Howard P. Venable, MD, (1913 – 1998), was born in Windsor, Ontario (Canada) but grew up in Detroit, Mich. It was here while attending Wayne State University to earn his medical degree — supporting himself during his training by working as a professional musician — that he became fascinated with ophthalmology. With no internship opportunities accessible to him in Detroit, Venable was eventually able to get an ophthalmology residency at Homer G. Phillips Hospital in St. Louis, Mo. — one of the few U.S. hospitals offering specialty training to black physicians. He went on to complete his residency at New York University In 1943, becoming the first African American ophthalmologist awarded a master of science degree in ophthalmology from the institution.

Venable returned to Homer G. Phillips Hospital to join the Department of Ophthalmology, where over the course of 36 years he mentored and taught over 100 residents, many of them African American students. He went on to chair the ophthalmology departments at three St. Louis hospitals and in 1958 also became the first African American faculty member at Washington University in St. Louis. When funding issues caused Homer G. Phillips Hospital to close in 1984, Venable and his wife, Katie, started the Venable Student Research Fund in Ophthalmology with the goal of encouraging more black students to join the ophthalmology field. The fund supported resident research projects and provided resources for necessary equipment and housing. Venable retired in 1987 and in 1994 was awarded the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Outstanding Humanitarian Award — the first African American to receive this honor.

(Photo credit: OBGYN-WUSTL)

Maurice F. Rabb Jr., MD, (1932 – 2005), is internationally recognized for his revolutionary work in cornea and retinal vascular diseases. Although a native of Kentucky, he attended Indiana University for his first two undergraduate years. When segregation ended in Kentucky in 1951, he transferred to the University of Louisville and was one of the first African American students accepted there.

After postgraduate training in New York, Rabb did his residency in ophthalmology at the University of Illinois Eye and Ear Infirmary, where he became its first African American chief resident. He went on to open a private practice in Chicago, Ill., specializing in retinal diseases. Rabb served in many roles throughout the rest of his career, including as as director of the Fluorescein Angiography Laboratory at the Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago, director of the Illinois Eye Bank and Research Laboratory of the University of Illinois Medical School, professor of ophthalmology at the University of Illinois College of Medicine, chair of the Department of Ophthalmology at Mercy Hospital, medical director of Prevent Blindness America and examiner for the American Board of Ophthalmology. He wrote five books, several articles and collaborated on a number of medical films. In 1995, he was nominated to the National Advisory Eye Council (NAEC) of the National Eye Institute. The Rabb-Venable Excellence in Ophthalmology Program is also named in his and Howard Venable's honor.

(Photo credit: SamePassage)

Patricia E. Bath, MD, (1942 - 2019), is renowned for her groundbreaking work in treating cataracts. After earning her medical degree from Howard University College of Medicine (Washington, DC) and interning at Harlem Hospital (New York), in 1969, Bath pursued a fellowship in ophthalmology at Columbia University (New York). It was during this time she observed health disparities among African American patients at two of the hospitals where she worked. This led her to conduct a study, the findings of wich revealed the burden of blindness among African Americans was nearly double the rate among Caucasians. Bath determined the cause to be a lack of access to ophthalmic care for many African Americans. Her findings led to the establishment of community ophthalmology.

Bath was the first African American ophthalmology resident at New York University, completing her training in 1973. In 1975, she became the first African American female surgeon at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Medical Center and the first female faculty member at the UCLA Jules Stein Eye Institute. The following year she co-founded the American Institute for Prevention of Blindness (AIPB). In 1983, Bath became chair of the Ophthalmology Residency Training Program at Drew/UCLA — the first woman ophthalmology program director in the U.S.

In 1986, she was the first African American woman to receive a medical patent for her invention, the Laserphaco Probe — a revolutionary surgical tool to vaporize cataracts using a laser, making it more precise and less invasive, which is used worldwide today. In 1988, Bath was nominated to the Hunter College Hall of Fame and in 1993 was named the Howard University Pioneer in Academic Medicine. That year she also became the first woman elected to the UCLA Medical Center’s honorary medical staff.

(Photo credit: National Library of Medicine)

Sources

MD, R. S. K. (2019, March 7). America’s first African-american eye specialist: David K. McDonogh, MD. American Academy of Ophthalmology.

America’s first Black Ophthalmology and otolaryngology specialist. New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai. (n.d.).

Dr. Charles Victor Roman | The History of African Americans in the Medical Professions. (n.d.). Chaamp.virginia.edu.

Notable Alums. (2019, July 12). Development and Alumni Affairs.

Dr. Maurice F. Rabb’s Biography. (n.d.). The HistoryMakers.

History | Program for ophthalmology medical students, residents, fellows. (n.d.). Rabb-Venable.

Patricia Bath. Lemelson. (n.d.).

Ho, Dr. F. (2023, February 21). Focus on Eyes: Spotlighting three influential Black Ophthalmologists for Black History month. Florida Today.