Celebrating Black History

Ralph J. Hazlewood II, PhD ― Finding Your North: From Plant Genetics to Vision Sciences

Ralph J. Hazlewood II, PhD, is a genetic scientist by training. He graduated from the University of the Virgin Islands as one of the few black males with a degree in biology. With a passion for genetic research, he was awarded one of only three slots for a highly competitive human genetics fellowship at The Genome Institute at Washington University. From there, he ultimately chose to attend and received his PhD from the University of Iowa where he studied the human molecular genetics of blindness.

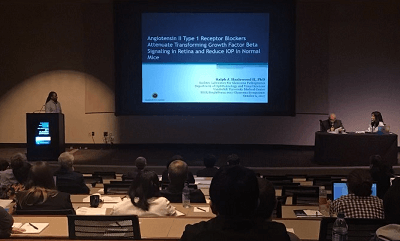

Hazlewood was awarded numerous accolades for this work including securing several prestigious awards and fellowships. He went on to Vanderbilt University Medical Center as a postdoctoral fellow where he made significant discoveries to repurpose existing FDA-approved drugs to treat and/or prevent glaucoma in rodents. Throughout this time, he also continually mentored the younger generation of underrepresented scientists.

Due to his experiences, Hazlewood was recruited as a program manager for Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc, in Tarrytown, NY, to manage and support target discovery and development of the ophthalmology pipeline. Currently, he is the senior manager for Regeneron Genetics Medicines, Program Management. His areas of study are ophthalmology, glaucoma, genetics, retina and neuroprotection.

Tell us a little about yourself

I grew up on the small island of St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands and was always fascinated by science. Not knowing much beyond being a medical doctor, naturally I wanted to be a physician. This changed while I was in undergrad during a plant physiology course field day where we stumbled upon an extremely rare plant species called Solanum conocarpum. My professor, a plant geneticist, extended an opportunity for me to do research exploring the plant’s genetic diversity, which ultimately led to it being added to the Endangered Species List. This experience solidified my interest to pursue a career in genetic research instead.

I was introduced to vision research during my first rotation in graduate school. For its small size, the eyes are one of the most important organs in our body. If you ask 100 people the question, which one of your five senses would be most deleterious to your life, losing eyesight would consistently be ranked number one or among the top. I ultimately joined John Fingert’s Lab at the University of Iowa where I harnessed the power of mendelian genetics to identify the first gene and mechanism of action for a rare blinding disease, similar to glaucoma.

What surprised you the most when you started out in this field?

One welcomed surprise within the vision sciences is the community. Almost every year I attend the ARVO Annual Meeting and I’m enthusiastic that I see familiar faces and am able to develop meaningful relationships with other investigators, scientists and trainees alike. This can at times feel like an extended family in our pursuit to fight blindness. Additionally, being able to connect with patients and learn about their experiences dealing with disorders that affect their vision has always been extremely motivating to help identify new treatments.

What is your greatest achievement?

As an early- to mid-career scientist/professional, one of my greatest achievements is attaining my PhD. Earning my PhD also holds additional exceptional value because it is a dedication to my first mentor, my mom. My mom sacrificed and made sure I was afforded almost any opportunity to explore my interests and had fostered a culture of learning for her kids to see the world beyond the Virgin Islands. Unfortunately, early in my graduate studies, I lost my mom, but attaining my PhD demonstrates my commitment to her teachings and to continue striving for excellence in patient-based research.

Have you encountered obstacles throughout your career?

Growing up in the U.S. Virgin Islands, I know firsthand the difficulties Black people and other minorities face, such as overcoming “imposter syndrome” and the “n of 1” or tokenism experience. I am also keenly aware of my accent and how I may be perceived because of how I wear my hair. However, it’s a conscious choice for me to work against the other narratives and to normalize seeing more diverse persons in the industry.

In your opinion, what obstacles do members of the African diaspora still face in this industry?

All too familiar for many Black scientists is the 'n of 1' experience. In many instances, as one progresses in their career, the number of people who look like you in your classes, teams and/or workplace dramatically diminishes, where one becomes the only person of color or minority. This often leads to feelings of inadequacy or being an imposter and not deserving of the opportunities/accolades you have achieved.

In one example, while wrapping up my postdoc research, I remember interviewing at a biotech company for a scientist position. While waiting in the lobby for my escort to take me to my first interview, I was approached by someone who asked me to hang up their jacket for them, although I was clearly dressed in a suit and using a laptop. This simple (and maybe unconscious) assumption that I did not belong within this space as a scientist underscores the feelings of imposter syndrome that are experienced by many minorities throughout their careers. This feeling of being the only one or one of a few Blacks in spaces throughout our careers adds an additional degree of pressure for representation and success.

In one example, while wrapping up my postdoc research, I remember interviewing at a biotech company for a scientist position. While waiting in the lobby for my escort to take me to my first interview, I was approached by someone who asked me to hang up their jacket for them, although I was clearly dressed in a suit and using a laptop. This simple (and maybe unconscious) assumption that I did not belong within this space as a scientist underscores the feelings of imposter syndrome that are experienced by many minorities throughout their careers. This feeling of being the only one or one of a few Blacks in spaces throughout our careers adds an additional degree of pressure for representation and success.

Have you noticed changes in the field as you advanced?

Over the last few years, and mainly due to the unfortunate events surrounding the murder of George Floyd and other Black Americans, I am more enthusiastic that there appears to be meaningful efforts across the industry to alleviate some of the obstacles faced by Blacks and other minorities. For example, there are concerted efforts by the biotech and pharmaceutical industry to build pipelines to increase representation. We know there have been numerous studies that show increasing diversity leads to increased productivity. I think it’s important for the field to not just increase numbers of diverse candidates, but to take a holistic approach by stepping back from simply looking at gender, race, and ethnicity. Also recognize that people are more than one visible aspect of their identity.

Additionally, finding mentors/role models is important to help with not only hiring but retention. Mentorship has played an important role in my career as I was fortunate to have mentors that have introduced me to new areas of STEM and expanded my world outside of medicine. As an inherent introvert, I realized that mentorship or access to mentors shouldn't be a barrier to career/professional development as we may inadvertently silence some of the greatest minds. New and ongoing initiatives that I’ve been involved with both as a mentor and mentee, such as the Scientists Mentoring and Diversity Program (SMDP), which strives to pair ethnically diverse students and early-career researchers with industry mentors; or the Better Workplace Initiative at Regeneron which aims to hire, develop and advance people with unique and diverse perspectives, all serve to address some of the obstacles that Blacks and other minority groups face in the industry.

Additionally, finding mentors/role models is important to help with not only hiring but retention. Mentorship has played an important role in my career as I was fortunate to have mentors that have introduced me to new areas of STEM and expanded my world outside of medicine. As an inherent introvert, I realized that mentorship or access to mentors shouldn't be a barrier to career/professional development as we may inadvertently silence some of the greatest minds. New and ongoing initiatives that I’ve been involved with both as a mentor and mentee, such as the Scientists Mentoring and Diversity Program (SMDP), which strives to pair ethnically diverse students and early-career researchers with industry mentors; or the Better Workplace Initiative at Regeneron which aims to hire, develop and advance people with unique and diverse perspectives, all serve to address some of the obstacles that Blacks and other minority groups face in the industry.

Where do you see yourself in five years?

In five years, I hope to be well positioned to continue being authentic and build meaningful relationships with a new network of colleagues within vision sciences, with the ultimate goal of identifying novel medicines, treatments and possibly cures for patients with blinding conditions.

What is the best advice you ever heard and abide by?

I draw on the quote from the former president of Liberia Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, “If your dreams don’t scare you, they’re not big enough.” I strive to always dream big and work hard to achieve my dreams. At seminars, I give students this same piece of advice. Find your north and don’t be afraid to try new things and experiences. You may realize that you can have a similar or bigger impact outside the norm by exploring all your interests.

What does Black History Month mean to you?

This month represents an opportunity for others to think about the important contributions of Blacks and Black Americans. It is an opportunity to shy away from the 'n of 1' narrative that only a handful of great minds/leaders have contributed knowledge to our collective species. It gives me an opportunity to remember scholars like Dr. Percy Julian, who pioneered chemical synthesis of medicinal plants, or Dr. Patricia Bath, an ophthalmologist who invented the Laserphaco Probe for cataract treatments. It gives me warmth that I can continue to be inspired by those before me and to inspire the next generation of Black scientists and research professionals alike.

“The statements made in this article are of my own and do not represent or propose to represent Regeneron Pharmaceuticals or affiliates.”

-Ralph J. Hazlewood II, PhD